By Shaun Caton

I know a man that makes always Smell to the people a smell calld -Groudlisquicki He loves you very much and will send you in a paper 3 bad smelling bousems or some bad smellings eare.

Princess Marie Bonaparte (1882-1962)

French author and psychoanalyst closely associated with Freud

Five Copy Books Vol. III (1952)

Through the convoluted distortion of memory, I attempt to recall a scene, arranged as series of transparencies inside a clunking slide projector, only to find the projections semi-obliterated and discoloured; fuzzy photographs that have now become reinvented as thoughtographs, teleplasmic traces, pictures in the mind’s eye that seem to form the fragments of an unreliable story.

The setting is a small front garden in Flodden Road, in the early 1980’s. Displayed within a paved forecourt are a mass of dolls in varying stages of decay; leprous, jaundiced faces with brutally dented cheeks, glass eyes turned insanely inwards, sun bleached skin, hair rinsed grey by acid rain. This ghoulish cabal reminds me of the Palermo catacombs, with suspended mummies, their imbecilic peeling faces, matted hair flaked with plaster, grimacing in silent protest at the invasive eyes that parade in slow motion before them, expunged by the quivering glitch.

I traversed the street several times a day. The encounter with the grotesque garden always gave occasion for pause, as new additions emerged over the blur of time and seasons – soon it became festooned with gaudy plastic cemetery flowers and soggy eviscerated toy animals. Nobody ever spied the curator of this outdoor undertaking. Perhaps it was created under cover of dark – a nocturnal labour of love? Bulbous artificial fruits lay scattered on the patio as votive offerings to the effigies dangling from knotted, blackened strings. It was an ornamental feature of Italian Baroque gardens (I am thinking here, of the spectacular Giardino Giusti in Verona) to flourish a huge cornucopia of stone oranges, lemons and pears, as an appeasement to the gods that secretly lurk in the dank undergrowth.

Beneath the garden there is another world, a thrumming tuber matrix of enmeshed root networks connecting the living with the dead, writhing deep into the tentacular blackness, a circulatory system for the underworld. This microcosm is populated by insects, that criss-cross tangled highways and byways in frantic teeming hordes. Roots act as syphons, filters, and dynamos, pounding and pumping, giving succour to the plants that thrust above the topsoil, probing and poking through the cracks and fissures, winding their tendrils around poles and pedestals with promiscuous dexterity, gradually overwhelming and engulfing the place in a verdant, shimmering tapestry of weeds.

During one week in Spring I noticed a trickle of centipedes spewing from the mouth of one of the largest doll’s heads. This exodus may have been prompted by dislodging the colony that inhabited the cavity. A flurry of thousands of tiny legs quickly relocated to the comparative sanctuary under seldom moved bricks.

In 1985 I visited the infamous Islington Arts Factory, which was housed in a gloomy Victorian chapel. This run-down venue hosted many eclectic events: live performance art that routinely involved the stomping and grinding of corn flakes inside a pair of oversize wellington boots, whilst the nonchalant performer smoked a cigarette with a certain smirking arrogance. There were also interminable concrete poetry recitals given by misanthropic misfits wearing beer stained Tee shirts over voluminous bellies, avant-garde music concerts that were silenced by sudden power cuts, crudely edited Super 8 films and scratch video festivals.

I remember a jerky, hand operated, slide presentation augmented by a narrator. The images were actual photographs of people and places that had been scribbled over with felt tip pens in a vortex of alterations. Every picture was scored by a stylus in the clandestine vernacular of automatic, spirit writing. With no progressive narrative structure, it felt like an excursion into a rambling dream diary. Nevertheless, I found myself lured into this dreamscape by the monotonous intonation, with its abrupt stops, starts, and shifts in tempo – the delivery of an uncertain, tremulous orator. The profusion of images flickering on that screen reminds me of a striking painting from J. H. Plokker’s book: Artistic Self Expression in Mental Illness (1964). This rare publication is one of the first surveys of schizophrenic art with colour illustrations and period psychiatric commentary.

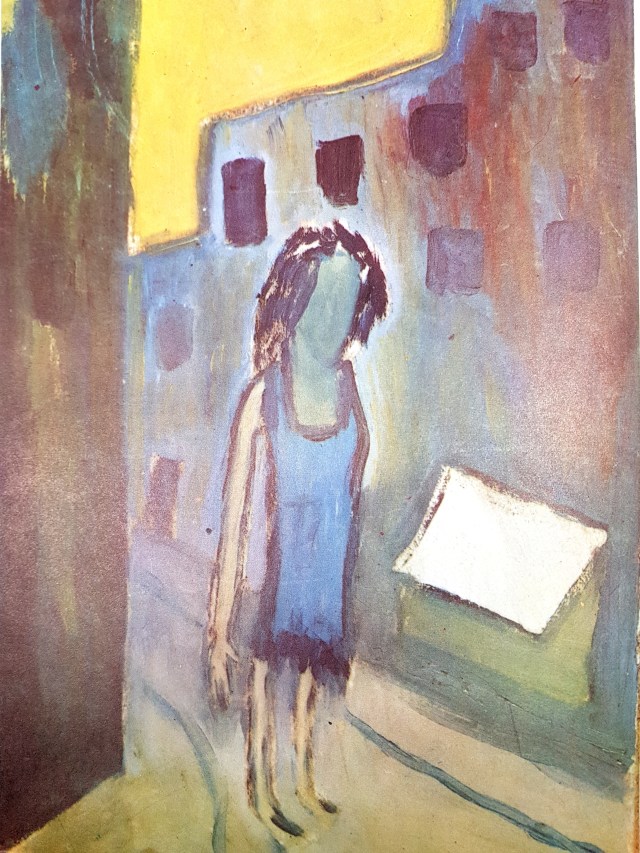

Plokker’s Figure in a street

A faceless green waif in a drab sloping street, with lopsided houses that could have been grafted from an expressionist composition, is captured by the brush of an unknown, unnamed painter. The book’s analysis of this picture leans towards social disintegration and isolation. It regards the use of putrid green and yellow to exemplify a feeling of dystopian dread and unease. I consider the figure in the street as a genderless being. It has abnormally long clawed arms and wears an all-in-one covering. Perhaps it is a post-apocalyptic mutant? The painting certainly emanates a loss of identity with the merging of the soft cityscape and the troll-like figure in the foreground.

Dream Fragment

8 February 2021

Shoreditch apartment. After years of hoarding. The entrance corridor is crammed almost to the ceiling with bin bags stuffed with unbearable refuse, unwanted clothing, shrivelled shoes. Acute difficulty with manoeuvring over this surface. Broken glass cabinet with stale bread crumbs, holes bored in the wood, eye sockets, scored graffiti faces leer. View from the window is mostly of factories. This is a gigantic photograph, not an actual scene. Chewing bread and rolling it in the palm of the hand to form malleable dough. This is fashioned into heads for veneration in a cult. A split tongue sputters unintelligible sounds over them.

The Man in the Poor House

Squirming at the corner of the eye, skittering shades of lives lived and exhaled. The ghost walker is not housebound, it stalks where ever I go. Dulled eyes are blackened with prophetic insights. Prophecies lurk in the thumbed creases of photographs, crumbling book spines; unwelcome truths yet to be revealed, lure us into the province of the chittering weevil.

A greatly deteriorated sepia photograph came into my custody and inspires multiple narratives. It shows an elderly bearded man with white hair, seated in a landscape, surrounded by four ramshackle wooden huts that may be latrines. In the background, there are a few spindly, leafless trees. The photograph is so feint that you must peer closely to discern even these details. On the back is written in a lilting graphite script: Man in poorhouse age 100. A portion of the image is now lost, leaving a whitish triangular shaped void that is a portal to another dimension. The subject resembles some medieval pilgrim and is bedecked in a gown, perched on a covered plinth that could be a stump. He glances to the side, not directly at the camera. Surrounding the picture there is an irregular mount, time worn, grubby and chipped. One can clearly envisage the many filthy hands that have held this photo, the blackened finger nails and cracked cuticles. This disintegrating portrait carries such a metaphysical presence despite its condition flaws, making us question the nature of capturing time and the persistence of fading apparitions. The feelings of abandonment and alienation the photograph conveys are similar to those delineated in Plokker’s Figure in a street.

Giving Up the Ghost

Before long everything will be organised; we await a very evil century. The state of the masked and the solitary ones greatly changed, few will find that they wish to retain their rank.

Nostradamus, Century Two

We met in a corner café. I do not remember her name. She was young and ultra-talkative in a bird like way. Told me it was her ‘dream job’. She had not long been in the post at the Romano – Germanic Museum in Cologne, before her induction was interrupted by a series of inexplicable happenings. These randomly occurred during the evening round of the galleries. Whilst checking the vitrines for bugs, she would suddenly intercept people with hideous, gaping wounds, bleeding, stumbling through dissipating smoke walls. They would appear and then almost instantaneously vanish. The curious thing was that they wore odd looking clothes. She explained that this was shocking at first. But in Mexico (her country of origin) people believed in spirits and had a sympathetic relationship with supernatural phenomena. Some of the people she saw had parts of their faces missing, burnt flesh and singed hair. Others sobbed. In order to understand why she saw these maimed bodies, it is necessary to look at the area in which the museum is situated – the zentrum.

Cologne was devastated by relentless bombing raids during the Second World War, with swathes of buildings razed and many civilians killed. The weird manifestations witnessed in the museum could be related to deaths that occurred in the 1940’s revealed as flashbacks, replayed like vintage film clips in faded colours, on an endless loop. The museum does not give up its ghosts easily.

Bone Emporium

Chapel Street Market, Islington, London. The curvaceous Victorian gold lettering spells out Cohen’s Furrier and Costumier above the shuttered window. But this establishment does not sell garments any more, it specialises in mummification and ossification, beak and claw taxidermy, and an ever increasing layer of long settled dust. On entering, I am greeted by a tiny octogenarian with a ragged shawl tightly wrapped around her skeletal shoulders. Her hair is dyed a faded tangerine and eyebrows have been pencilled in quizzical arches that meet to form an M when she frowns. She looks like someone who might inhabit the child-like painted street in J. Plokker’s book, hiding behind piles of bone.

May I help you?

I glance around this ossuary of animal, bird and fish trophies, each occupying their glass fronted sarcophagi with cracked painted interiors, dried flora, stones and shells glued crudely in place. These ex-creatures are now dessicated, seeping a virulent varnish from their stitched, cured skins. Cobwebbed skulls and antlers mounted on long forgotten plaques commemorate the grand day of the hunt in 1927. Everywhere there is bone dust, a yellowish powder that exudes the peculiar mustiness of death. My gaze falls momentarily upon a monstrous catfish, its feelers like two withered antennae stretching out to beckon me into its brittle, xylophonic world, full of unexpurgated river stone dreams. How much is that? The answer is nearly always the same – £40. It’s as if the crone of this emporium can only remember one figure. But few people come into this mausoleum and even less purchase anything. This gives me the negotiating upper hand. How about 3 heads for £40? You’re robbing me blind, but times ain’t as good as they used to be, so let’s say £50? I turn towards the door. The woman gives me the telescoping querulous glance peculiar to one about to lose a deal. With a heavy sigh £40 is agreed. I leave with the trio of stuffed fish heads wrapped in crumpled brown paper tied with raffia.

White Island

Summer 2010

Location: A tiny uninhabited island, in Lower Lough Erne, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reach White Island, I managed to convince a bemused boatman to take me out to this remote place, populated only by sheep. Why do you want to go there?’ he asked with an air of incredulity.

If only you knew…

In the reconstructed open knave of a church, there is a wall with 8 stone figures that date between 800 – 100 AD. They have very large jutting chins and tiny oval eyes set close together, long aquiline noses, tonsured heads, hoods and cloaks. One carries a small shield, another holds a crosier and a bell. They could be representations of monks, abbots, or saints. One is certainly a Sheela-Na-Gig. The ribald exhibitionist who flouts her open vagina to the unexpected visitor who lands on this shore, as if daring them to enter this enchanted grove. An undefined figure remains unborn, never fully carved from its block. This rudimentary, featureless effigy is accompanied by an adjacent single forlorn head for company. So what of this congregation of abandoned souls in stone? These sentinels were salvaged between the years 1830 – 1958 when they were impregnated into the wall as a group of spiritual guardians. Nearly all of them have nasal pinch marks, hinting at an inner serenity and the potential for laughter. They stare silently back, through centuries of weather and the ever encroaching spots of turquoise lichen. If we make connections with art we have experienced in our time (Cubism, folk and outsider art) does it enliven our communion with these other worldly wayfarers? Will they break their long silence and speak to us through dreams, charting their scars on the city’s cold sleeping brow? Can we reanimate a notch for knowing them and determine an image of their origin?

Cut it Out

17.30 hrs Hoxton 2021

I am travelling home on the 394 bus through the deserted existential city, with its nocturnal portals covered in grime, boarded up shop fronts, wind-blown rubbish making a scuttling score for the cyclonic curfew hour, puddles reflecting the ruby orbs of oncoming traffic. Beyond the misted windows, disembodied voices speak in a language of dissonant hieroglyphics: barks, estuary consonants, moaned bass blah blah’s. The journey is nearly always uneventful and tedious.

A grey man seated in front of me pulls some paper from his bag and begins shearing the edges with scissors, snipping this way and that, trimming feverishly, as one might cut a mass of tousled hair. My curiosity increases as I watch him form little figures with crude features, each taking on its own personality in a collapsing concertina of jiggling dancers. Then, with an apparent change of heart, he stuffs these paper cut outs into his holdall, yawns and rummages for a plastic bottle containing cold milky tea. Gulping the liquid down greedily, he then turns to stare at me, emitting the most phenomenal belch I have ever heard.

Marie

Princess Marie Bonaparte (1882-1962) was a French aristocrat, author, and Freudian psychoanalyst. In 1952 she self-published her juvenile exercise books of 1892, complete with facsimiles of drawings, stories, and fantasies. Applying psychoanalysis to her fusion of dreams and memoirs, Bonaparte evinces a deeply erotic explanation that veers towards the morbidly obsessive. As curiosities, these cryptic books make peculiar reading, taking the reader into the zone of a voyeur or eavesdropper. Written in French, English, and German, they coalesce to form an imaginary language, that is both phonetic and spontaneous. These appear like experimental prose poems and require multiple readings to glean any rational sense or meaning.

London November 2020 – March 2021